By David Klein

In our last blog on affordable housing, we discussed how subsidized vs. unsubsidized housing contributes to more affordable housing overall. But there was a key process we’ll be diving deeper into in this blog.

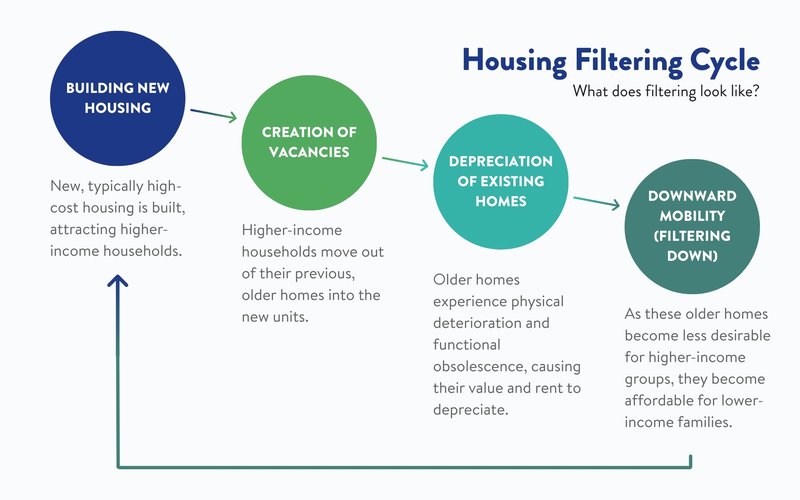

One of the most misunderstood parts of housing economics is a process called “filtering.” It’s the process where yesterday’s new housing becomes today’s more affordable housing.

Here’s how it works: when new homes are built, often at higher price points, they create room for people with higher incomes to move into those newer units. Over time, the older homes that were moved out of, in favor of the new homes, become available for other renters or buyers at slightly lower prices. This steady churn is how most unsubsidized affordable housing actually emerges.

Think about an apartment building constructed in 1990. At the time, it might have been marketed to high-income professionals. But 35 years later, it’s no longer considered “luxury.” The finishes are dated, the appliances older, and the rent, relative to newer buildings nearby, has become accessible to middle-income families. That’s filtering in action.

But there’s a catch: filtering only works when enough new homes are being built to meet demand. If new construction is blocked or delayed, the people who would have moved into those newer homes compete for older units instead, driving up prices and pushing lower-income renters out. Research from the Pew Charitable Trusts and the Upjohn Institute shows that when cities expand their housing supply, rents in nearby older buildings rise more slowly or even fall compared to areas with little new homebuilding.

Filtering isn’t about “trickle-down” economics, it’s about supply dynamics over time. Housing is durable: it lasts for decades, and as it ages, it naturally becomes more affordable if new homes keep entering the market. That’s how cities like Minneapolis and Tokyo have managed to stabilize or even reduce rents despite growing populations; they allow continuous construction across price ranges.

A simple way to picture it:

But don’t we eventually run out of space?

It’s a fair question, and one of the biggest misconceptions about building more housing. Even in states often described as “built out,” like California or Massachusetts, the issue isn’t that there’s no land left, it’s that most residential land is zoned for only one home per lot.

In many major metro areas, 70–80% of residential land is reserved exclusively for detached single-family homes. That means we’re effectively banning apartments, duplexes, and small multifamily buildings from most neighborhoods, even though those take up the same footprint as one house.

Filtering doesn’t rely on endless outward expansion. In fact, the most sustainable version happens through infill and redevelopment which involves replacing older, smaller buildings with slightly larger ones as demand grows. Think of a single home becoming a triplex, or a one-story strip mall being replaced with a mixed-use apartment building that includes housing above shops.

And there are countless ways we can add homes without using new land:

- Converting old office buildings or hotels into housing.

- Allowing backyard cottages (ADUs) and duplexes on existing lots.

- Redeveloping underused parking lots or commercial corridors.

In short: The bigger problem right now isn’t lack of space, it’s decades of policies that artificially limit the homes we can build on the space we already have.

When we fix those rules, filtering can work the way it’s supposed to. Each new home helps relieve pressure throughout the system, keeping cities affordable not just today, but for generations to come.

But if the process is so straightforward, why do so many people still oppose new housing? Much of the resistance comes from persistent myths about what actually makes homes affordable. Let’s unpack a few of the most common ones.

Common Myths About Affordability

Conversations about housing affordability are often filled with misunderstandings that stall progress. Many of these myths come from a place of genuine concern, but they’ve also been used for decades to justify blocking new homes. Let’s unpack a few of the biggest ones.

Myth #1: “Market-rate housing only helps the rich.”

It’s easy to assume that new, higher-end homes only serve wealthy buyers or renters. But the truth is that when we don’t build new housing, the wealthy compete for older, more affordable units, and win.

Without a steady flow of new supply, high-income households simply bid up the cost of existing homes, squeezing everyone else out. That’s why cities with severe housing shortages, like San Francisco or New York, see older buildings renting for luxury prices. When new homes are built, however, those higher-income households have somewhere else to go, reducing pressure on the rest of the market.

This filtering process is how most affordability emerges over time. Even though new buildings may start out expensive, they make room for everyone else down the line. The alternative, freezing new construction, locks scarcity in place.

Bottom line: Market-rate housing isn’t the only solution, but it’s a necessary part of any solution. Without it, the wealthy simply outbid the middle and working class for the same limited homes.

Myth #2: “We can solve this with subsidies alone.”

Subsidies are vital, they provide stable homes for low-income families who the market will never serve on its own. But the scale of our national housing shortage makes it impossible to rely on subsidies alone.

Right now, federal rental assistance reaches only about one in four households who qualify. Millions of low- and middle-income families remain cost-burdened because there simply aren’t enough units at any price level. Building more market-rate housing helps close that gap by keeping prices in check across the board.

It’s not an either/or equation. To truly tackle affordability, we need both: deep subsidies for the lowest-income households and abundant private homebuilding to prevent scarcity in the first place.

Myth #3: “Affordable housing will hurt property values.”

This fear has been used for decades to block affordable housing projects. But research consistently shows it isn’t true. Studies from the National Association of Realtors, Trulia, and UC Irvine have all found that well-designed, well-managed affordable housing developments have no negative effect, and sometimes even small positive effects, on nearby property values.

Inclusionary and mixed-income developments can actually stabilize neighborhoods by reducing vacancies, improving infrastructure, and supporting local businesses. In places like Denver, Seattle, and Austin, adding affordable and market-rate homes together has created thriving, walkable communities that attract both longtime residents and newcomers.

Housing stability doesn’t bring down a neighborhood, it strengthens it. The only real threat to our neighborhoods isn’t new housing, it’s not enough housing.

That’s why confronting housing myths matters. When we replace fear with facts, we make room for solutions that actually work: more homes, lower costs, and stronger communities. We need more homes, not more hesitation. Get involved in the movement to solve our national housing shortage by joining your local YIMBY Action chapter or subscribing to our email list to take action in your community.